BY KIERAN LINDSEY, PhD

Is there any non-human skill people covet more passionately than the ability to fly?

Understandably, early aviation experiments centered around mimicry of birds, complete with flapping arms that were usually covered in feathers. The Greek legend of Daedalus and Icarus is a familiar example, but plumage continued to be part of the trial-and-error approach through the first years of the 19th century, when a tailor named Albrecht Berblinger constructed an ornithopter and then took an ill-fated plunge into the Danube. Those daring young men with their dreams of flying machines… they just didn’t understand the concepts of thrust, lift, and drag, and they couldn’t let go of the idea that soaring requires feathers.

Understandably, early aviation experiments centered around mimicry of birds, complete with flapping arms that were usually covered in feathers. The Greek legend of Daedalus and Icarus is a familiar example, but plumage continued to be part of the trial-and-error approach through the first years of the 19th century, when a tailor named Albrecht Berblinger constructed an ornithopter and then took an ill-fated plunge into the Danube. Those daring young men with their dreams of flying machines… they just didn’t understand the concepts of thrust, lift, and drag, and they couldn’t let go of the idea that soaring requires feathers.

I guess Saturday mornings with Rocky and Bullwinkle were not a part of their childhood.

Skip ahead in the history books about two hundred years, during which heavier-than-air flight went from foolish fantasy to fleetingly airborne, to semi-reliably aloft, to acrobatic enough to decide the outcome of a World War, to commonplace as ~30,000 commercial flights per day in the U.S. in 2017.

And yet…

Aviation advancements and inventions during the greater part of the industrial age were about balloons and dirigibles and planes, i.e., aircraft; human beings remained firmly planted on terra firma unless they could climb inside or hang from some kind of apparatus.

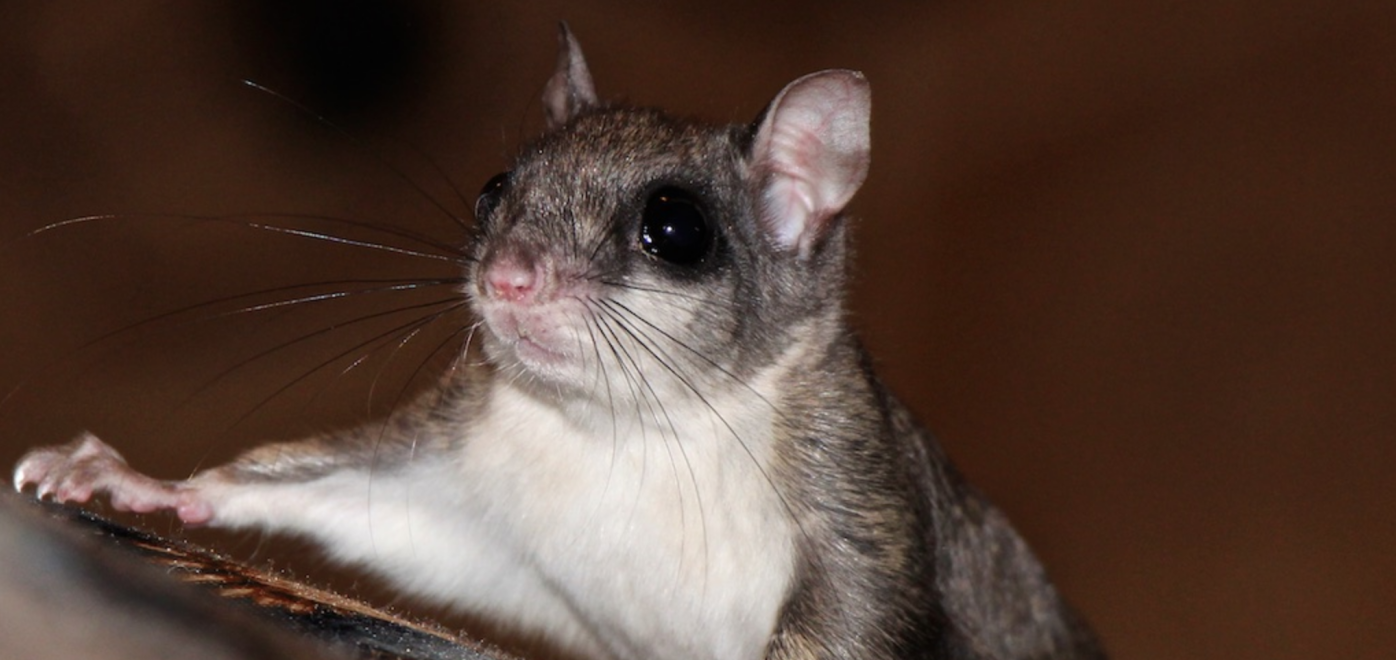

It’s hard to point to a specific aeronautic adventurer as the first to see a flying squirrel, recognized the similarities with their fellow mammal, connected the dots, and think, “Eureka! A wingsuit!” But no one lucky enough to have seen one of these big-eyed nocturnal windsurfers could fail to notice the resemblance to the modern flying suits that have finally allowed human beings to fly free as a bird squirrel, unencumbered by gondola, scaffolding, or fuselage.

A long, flat tail is critical for controlling that fall. Serving as a rudder, it allowing 90 degree turns around mid-flight obstacles. The tail is used for landing, too; on the approach, the tail is raised to an upright position while, at the same time, all four limbs move forward to form a kind of patagium parachute. Together, these actions create enough drag to tip the animal’s head and body up as it prepares for impact with a tree trunk or branches, a bird feeder, or a building.

A long, flat tail is critical for controlling that fall. Serving as a rudder, it allowing 90 degree turns around mid-flight obstacles. The tail is used for landing, too; on the approach, the tail is raised to an upright position while, at the same time, all four limbs move forward to form a kind of patagium parachute. Together, these actions create enough drag to tip the animal’s head and body up as it prepares for impact with a tree trunk or branches, a bird feeder, or a building. The New World is home to three species of rodent flyboys and flygirls: Northern (Glaucomys sabrinus); the recently differentiated and designated Humboldt’s (G oregonensis); and Southern (G volans).

The New World is home to three species of rodent flyboys and flygirls: Northern (Glaucomys sabrinus); the recently differentiated and designated Humboldt’s (G oregonensis); and Southern (G volans).  There’s also range overlap between Northerns (found from Alaska to Nova Scotia down to Utah and North Carolina) and Humboldts’ (whose limit their travels from British Columbia down into southern California) as well. However, the two are close enough in physical appearance and behavior that it took an examination of their DNA before scientists realized earlier this year (May 2017) that they were looking at not one species, but two. Humboldts’ have been described as smaller and darker than Northerns, but the fact that it took so long for the former to be recognized as distinctive (Southerns were first described in 1758, Northerns in 1801) suggests to me that one would have to do a mighty up-close-and-personal examination to make a positive ID.

There’s also range overlap between Northerns (found from Alaska to Nova Scotia down to Utah and North Carolina) and Humboldts’ (whose limit their travels from British Columbia down into southern California) as well. However, the two are close enough in physical appearance and behavior that it took an examination of their DNA before scientists realized earlier this year (May 2017) that they were looking at not one species, but two. Humboldts’ have been described as smaller and darker than Northerns, but the fact that it took so long for the former to be recognized as distinctive (Southerns were first described in 1758, Northerns in 1801) suggests to me that one would have to do a mighty up-close-and-personal examination to make a positive ID.